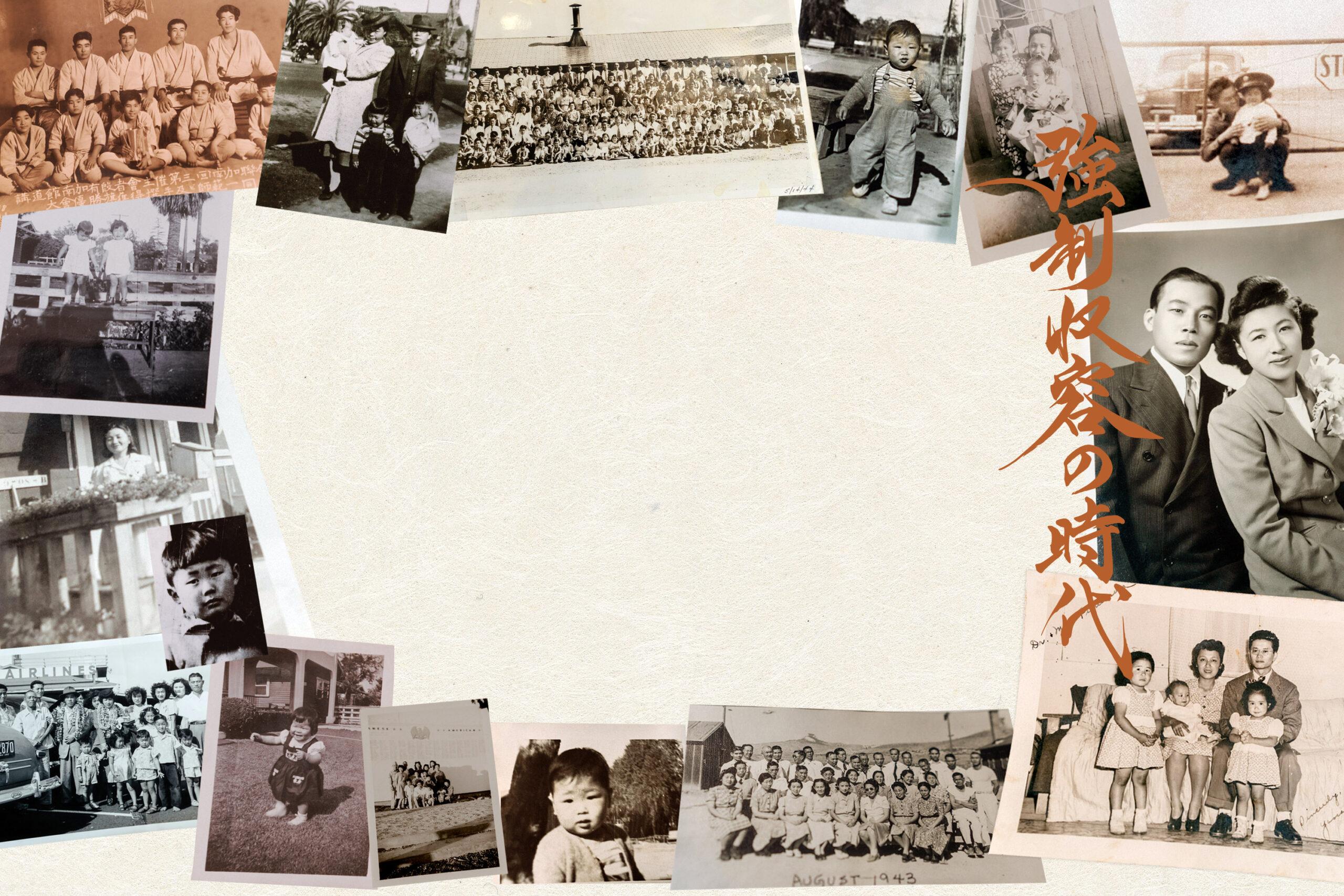

During World War II, the U.S. government invoked the Alien Enemies Act, ultimately incarcerating more than 125,000 people of Japanese descent — including many American citizens. The act uprooted and split families, causing them to abandon their homes, businesses, and communities.

It has been 80 years since the war ended and they were released. In these testimonies, nine of the last survivors of Japanese American incarceration reflect on their stolen youth and how this injustice impacted the rest of their lives.

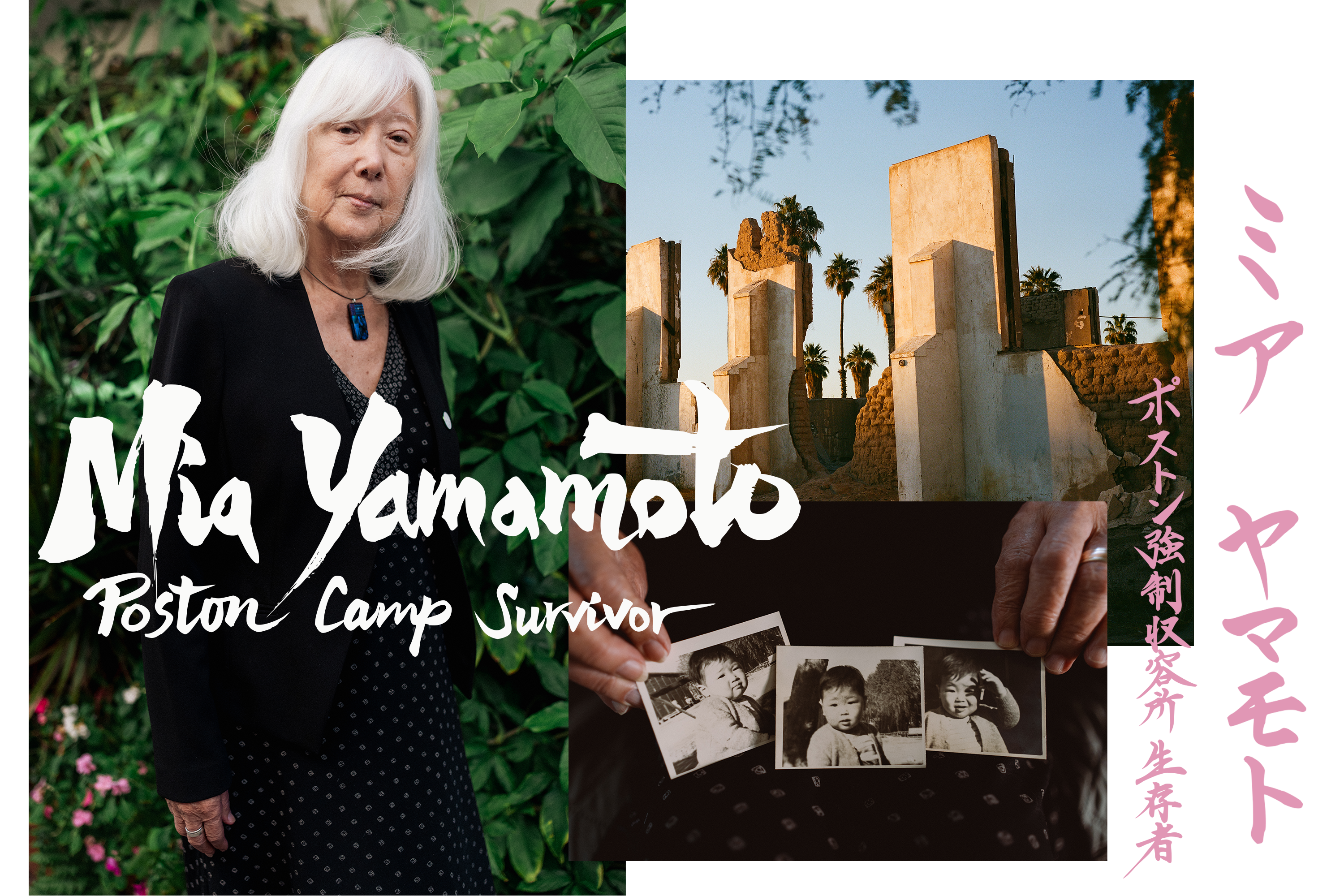

It’s November 2023 in the Koreatown neighborhood of Los Angeles, and Mia Yamamoto has arrived at the house that her late mother lived in for more than forty years, which she’s preparing to sell. Still dressed in a skirt and blazer, the then-80-year-old criminal defense attorney has just come from work. Her trailblazing California law career spans decades, and even out of the courtroom, surrounded by cardboard boxes, she speaks in eloquent paragraphs. When asked about the purpose of a life in law, she says, “The whole point is to do justice.”

“If we are not doing anything else in this work, in this profession, in this practice, making sure that we do justice is at the top of the list,” she tells me. “The only way it’s done is when we see injustice — to act, to speak, to march, to hold protest signs, to vote, to do these things to support a community — is to do the right thing.”

Yamamoto was born at a site of injustice — a World War II Japanese American incarceration camp in Poston, Arizona — so hearing her speak about fairness and the rule of law is especially powerful. Although many of her family photographs have already been packed away, several black-and-whites of herself as a toddler wearing overalls sit unboxed and available to view.

“I don’t remember the camp at all,” she says. “I have no recollection. I guess I got out of there when I was two or something, 1945. So I do have a recollection of the resettlement, where all of us were getting out of camp at the same time, and many of us tried to go back to the same places along the West Coast and try to rebuild [our] lives from there.”

Yamamoto has spent much of her life rebuilding from her family’s wartime experience. She grew up in postwar Los Angeles, an actively hostile environment for Japanese Americans. She learned from her mother that her father, the first Asian American graduate of Loyola Law School, had called the camps unconstitutional. The incarceration’s aftermath manifested within her a deep desire to help others fight injustice.

Yamamoto represents the dwindling last generation of Japanese American camp survivors — people now age 80 and older who were children, toddlers, or infants during this often-neglected chapter of American history.

Many Japanese American detainees chose not to speak about their incarceration, even to their children. But these nine individuals are sharing their experiences so current generations can learn from them. Once the last of the survivors dies, it’s uncertain how Americans will remember this history. As a photographer and videographer — someone who is driven to preserve moments of history — I set out to interview them upon realizing that now, more than ever, it’s vital to re-examine the past so we can better understand the darkness that’s gripping the present.

Anti-Japanese legislation and racism began decades before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, a fact often underreported in U.S. history books. Yet for more than 125,000 Japanese Americans, most of whom were residing along the West Coast, December 7 was the impetus for their worlds collapsing.

Within hours of the attack, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt — who deemed anyone with Japanese ancestry, regardless of citizenship status, a threat to national security — invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, a wartime power not employed again until March 2025, when President Trump used it to deport Venezuelan immigrants. On February 19, 1942, Roosevelt also signed Executive Order 9066 directing the U.S. military to uproot Japanese Americans from their homes and place them in incarceration camps across the West Coast and as far east as Arkansas.

The 10 main camps on the U.S. mainland were Amache (Colorado), Gila River (Arizona), Heart Mountain (Wyoming), Jerome (Arkansas), Manzanar (California), Minidoka (Idaho), Poston (Arizona), Rohwer (Arkansas), Topaz (Utah), and Tule Lake (California). In addition to the camps, 15 temporary detention centers (which the government more benignly called “assembly centers”) were set up to process the arrival and transport of Japanese Americans, each arriving with only what they could carry.

In the days leading up to Japanese Americans’ departures to the various camps, confusion, sadness, and anger hung like a dark cloud over their collective future. FBI agents routinely spied on them. For many, a numbing feeling of despair increased each day. From March to August 1942, the federal government issued 108 Civilian Exclusion Orders, often accompanied by posters emblazoned with the words “Instructions to All Persons of Japanese Ancestry.” These orders, which were stapled to telephone poles and posted in other public places along the West Coast, gave Japanese Americans one week’s notice to leave their homes and report to Civil Control Centers for relocation.

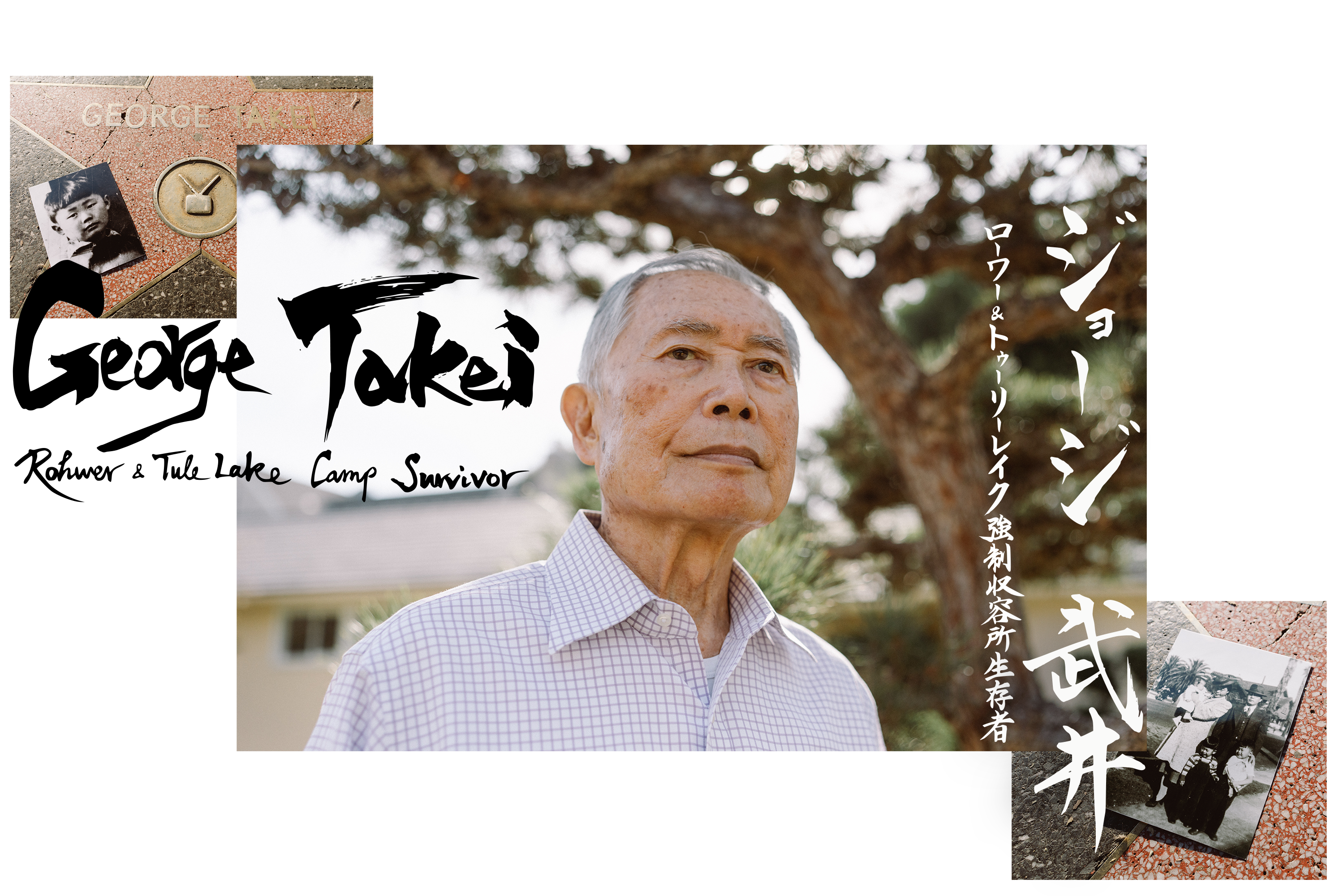

George Takei, 88, is a survivor of Rohwer and Tule Lake. His many fans know him best for his role of Lieutenant Hikaru Sulu on “Star Trek,” as well as for his activism as a member of the LGBTQ+ community. But his fellow incarcerees may recall Takei as a young boy in the camps who loved watching movies, which undoubtedly influenced his love of performance from an early age.

Takei talks of surviving that period through adventure, play, and curiosity about the outdoors. Throughout his life, he has recounted and written about the brave risks his parents took: His mother snuck in a prohibited sewing machine to make clothing for her children, and his father served as a block manager in the camp who resolved disputes and liaised with camp administrators, cementing himself as a leader in the community.

Executive Order 9066 had allowed Roosevelt’s secretary of war, Henry Stimson, the unyielding power to designate regions of the country as “military areas” where people deemed an enemy of the state wouldn’t be allowed. Executive Order 9102, signed a few weeks later on March 18, 1942, created the War Relocation Authority, a group within the Office of the President that was charged with carrying out the forced relocation.

Not all families were escorted out of their homes by soldiers; others arrived at their local train depot or staging center after all their belongings had been sold off for minuscule sums. They left behind homes, businesses in disarray, and bank accounts frozen — and eventually emptied — by the government. Their thriving communities, built brick by brick over generations, were left to the mercy of surrounding inhabitants.

The windows on the trains that transported Japanese Americans to the camps were boarded up or concealed with curtains. When I learned this fact, I felt a chill. As an American Jew, I had come to this story with a sense of kinship. This detail felt like an eerie parallel to the inconspicuous cattle trains that Nazis used to hide Jews while transporting them to concentration camps across Europe. My family members had emigrated to the U.S. before the death camps, but the grief of the Holocaust is something I’ve carried with me my entire life.

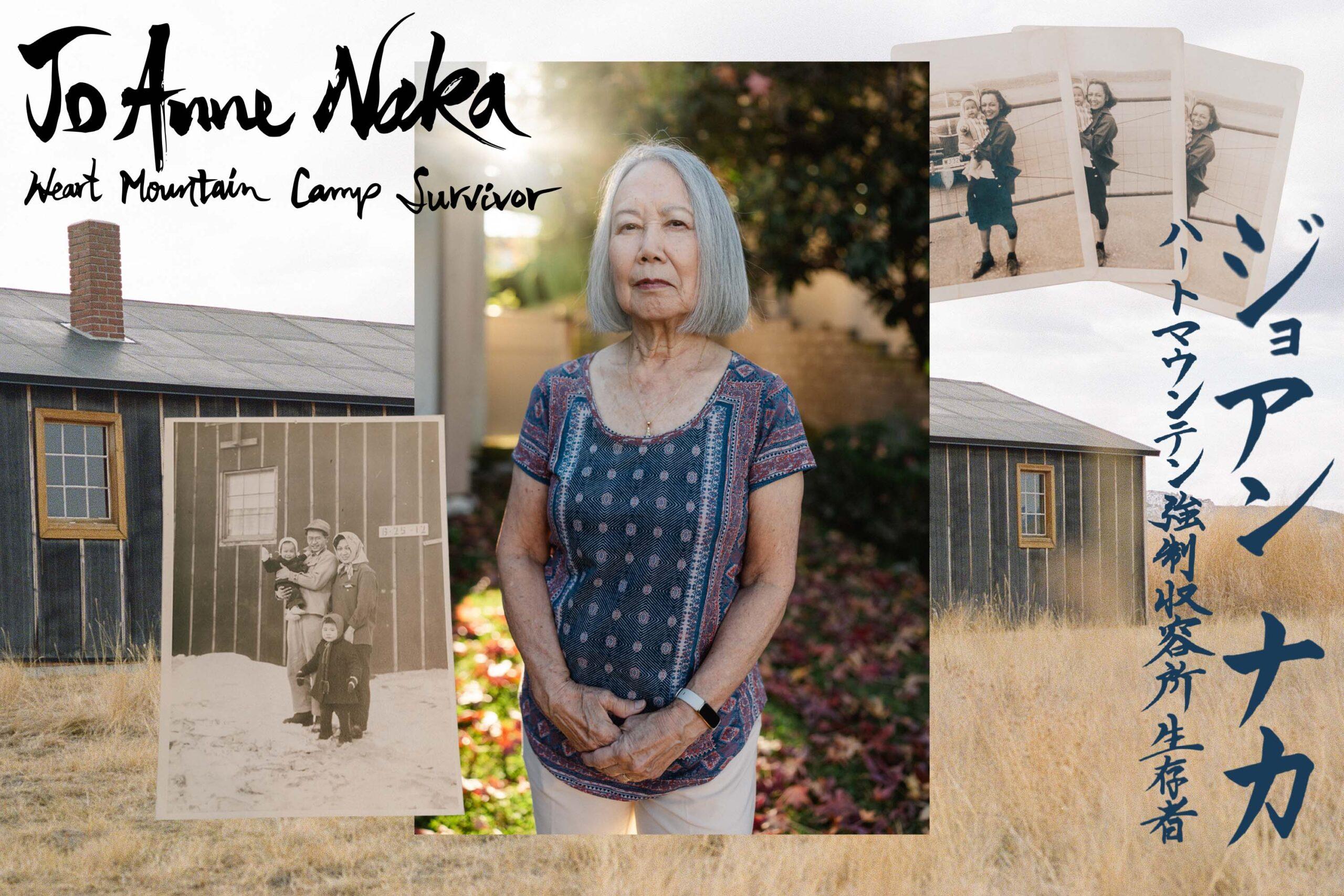

Jo Anne Naka is one of more than 14,000 people who were incarcerated at Heart Mountain. Sitting at her dining table, she showed me dozens of images of herself at the camp, from a newborn cradled by her mother to an energetic toddler searching for minnows in the river. It was the first time I had seen the growth of a small child against the backdrop of a barrack. Naka was vulnerable in these pictures, but in most of the portraits with her family at Heart Mountain, she is smiling.

Before Naka’s family was sent to Heart Mountain, they were held in stables at the racetrack at Santa Anita Park. Although I had grown up in Los Angeles, I never knew that racetrack had been a temporary detention center for Japanese Americans. I thought I knew World War II history, but details like these made me realize I have much more to learn.

When Japanese Americans arrived at the camps, the climate was often vastly different from their home environments, whether blistering Arizona heat, terrible dust storms in Utah, or brutal whipping cold of rural Wyoming. Their housing arrangements were often hastily constructed tar-papered barracks shared with other occupants. Families usually had one room to themselves with only a thin wall separating them from the living quarters of another family.

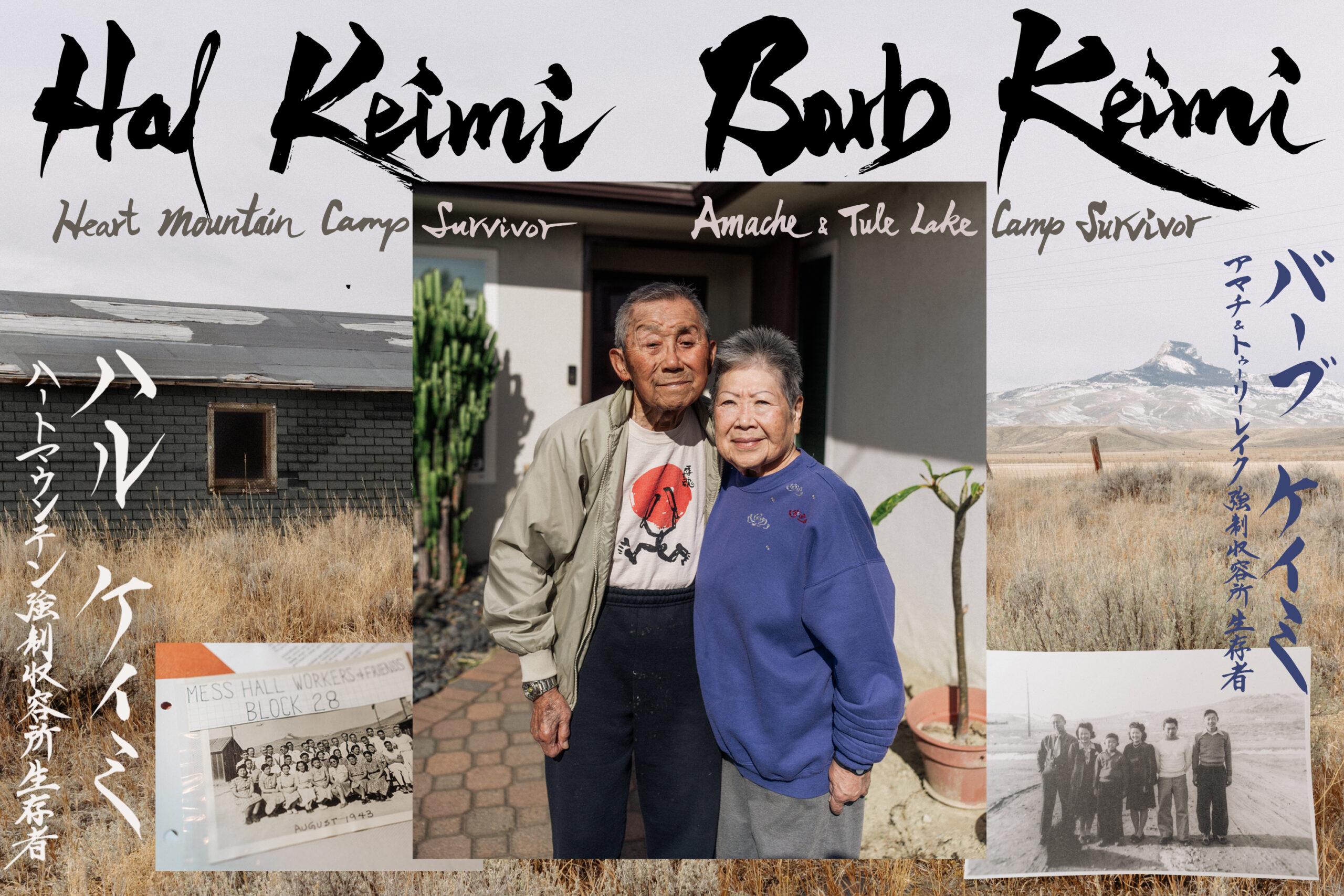

In almost all barracks across the camps, insulation was nonexistent or sparse. A pot-bellied stove, sitting among a single light fixture and some cots, is a poignant visual of their living space that stayed with these survivors. Former incarceree Hal Keimi remembers that the stove — the one appliance that kept families alive and warm — had a massive sheet of asbestos behind it.

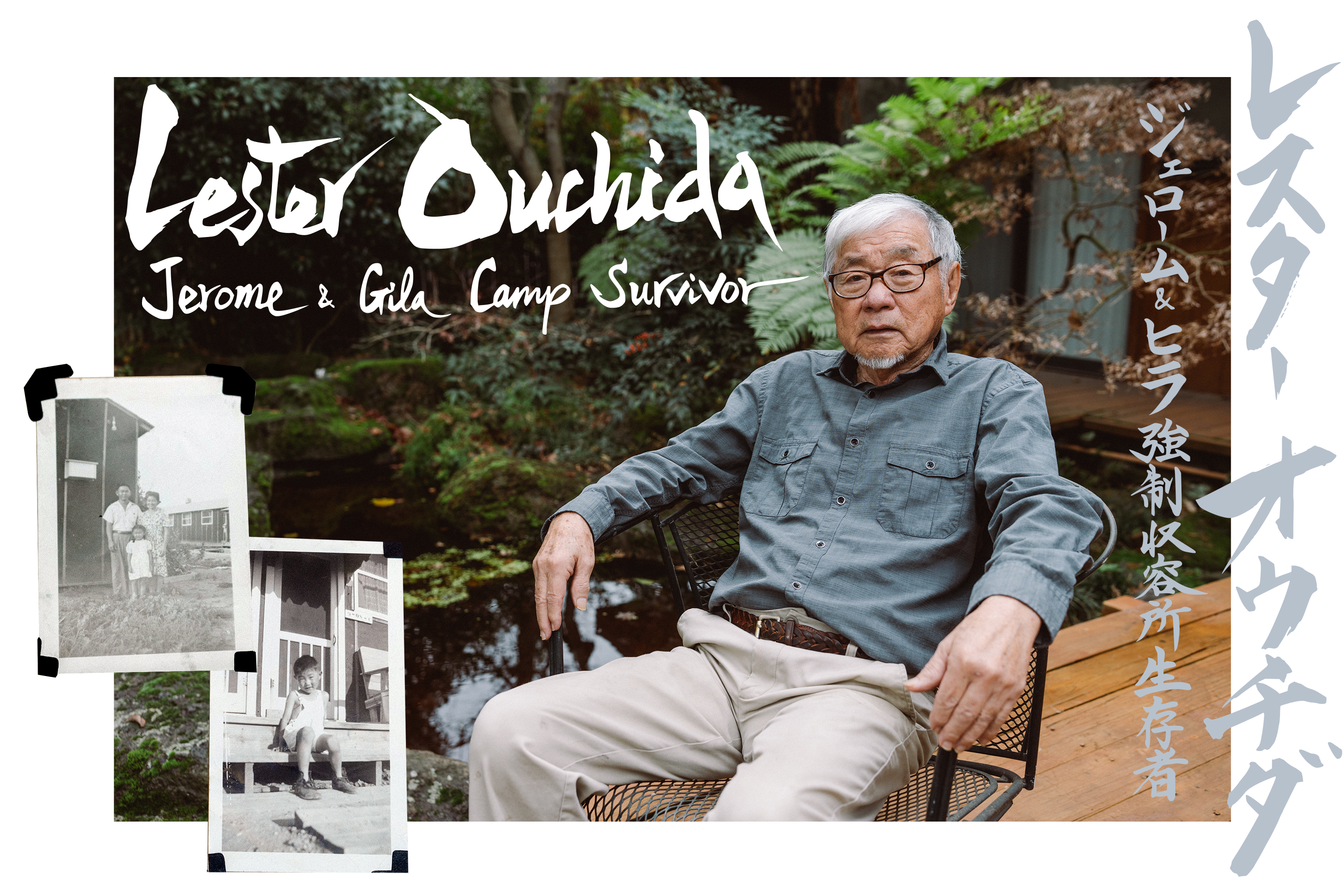

A mess hall was the main gathering space for daily meals, which changed the social dynamic of each nuclear family as many children drifted off to eat with their friends. The latrine for each block was communal for each gender, but without doors or separating walls for the stalls. One survivor of the Jerome and Gila camps, Lester Ouchida, recalls the chronic humiliation the women in his family experienced because of the lack of privacy in the latrines. When they used the facilities, they wore paper bags on their heads with eyeholes cut out to conceal their identities.

Hal Keimi is a survivor of Heart Mountain, and his wife Barb Keimi is a survivor of Amache and Tule Lake. They met at the University of Southern California when they were college students and still hold season tickets for football. The couple now lives in Monterey Park, California.

Even as barbed wire and guard towers became the universal backdrop, the inmates felt compelled to create community and a sense of normalcy. They built churches and schools and did the necessary work to maintain them and help the incarceration camp feel like home.

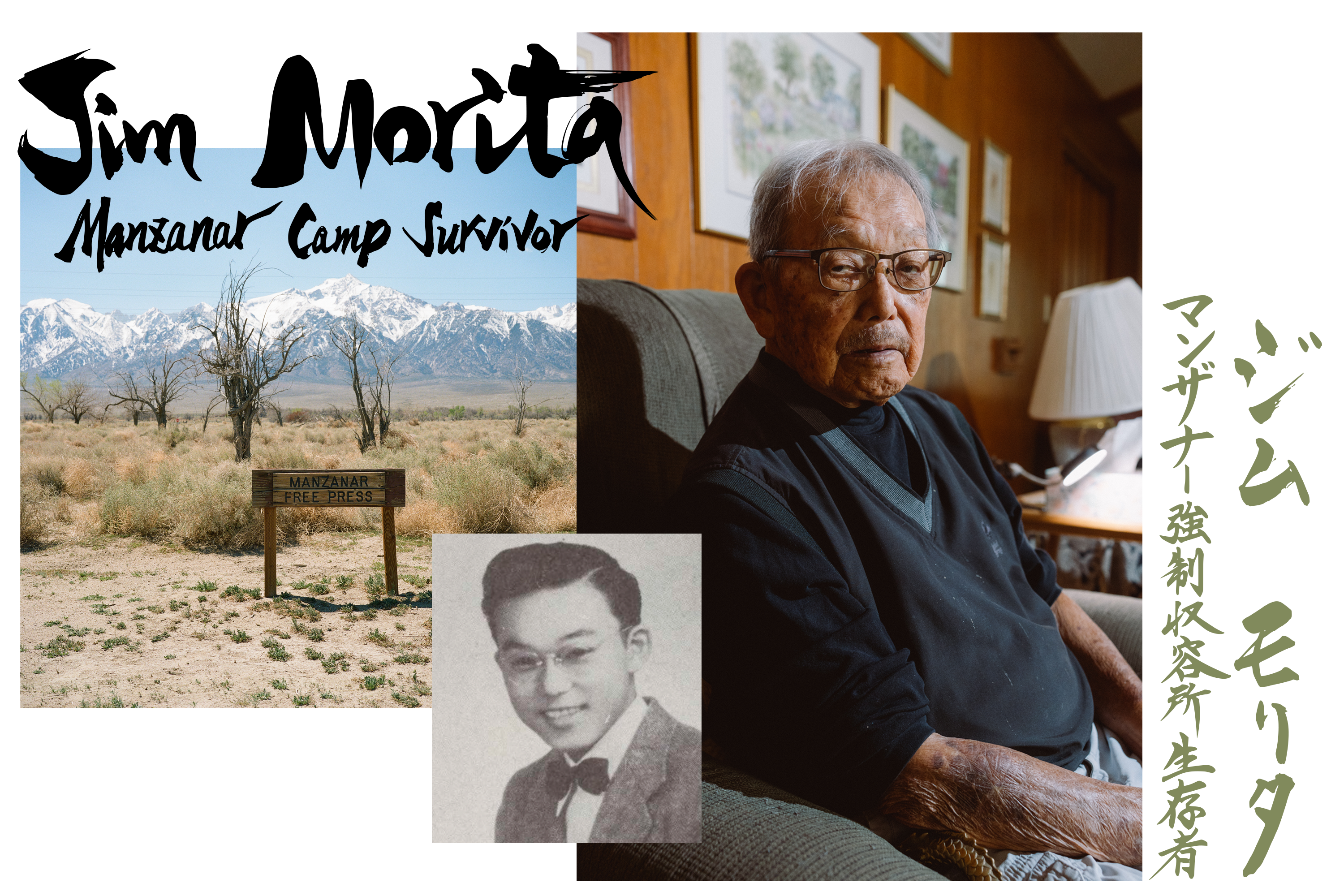

Jim Morita, a survivor of Manzanar camp, was a standout baseball player in the league at the 6,200-acre California camp. He celebrated his 99th birthday in December 2024 and still plays golf twice a week. He vividly recalls being sent to pick potatoes in Idaho because of the labor shortage during the war and taking jobs around the camp.

In addition to maintaining the camps, thousands of incarcerated Japanese American men were employed by local farms, which kept many of them away from their families for a significant period of time. Although work was not mandatory, many Issei (first-generation) women also opted to have jobs, in addition to family caretaking, so their days would pass more quickly. Their jobs paid very little, especially compared to what their free Caucasian counterparts earned. Work stoppages were held in several camps to protest unsafe employment and living conditions.

These survivors were either newborns or young children while incarcerated, but they said the experience sometimes felt like an unconventional summer camp because of the range of activities they shared. Their parents did their best to shield them from the daily traumas of incarceration, and in many instances athletics, like baseball, became an emotional lifeline for kids who had played in leagues back home.

The incarceration camps were not uniform in conditions or purpose. Interviews with survivors from various camps reveal that the flat, treeless Tule Lake camp was starkly different. This 1,100-acre segregation center (with an additional 3,500 acres of irrigated farmland) was used to punish and separate those deemed disloyal to the U.S.

With a bigger military presence, overcrowding, and consistent unrest because of dehumanizing conditions, Tule Lake had a violent environment. In late 1943, martial law was declared in the camp. Nearly 30,000 people were detained, and the camp eventually included an on-site jail and a stockade. Its demographic of “resisters” included community leaders, Buddhist priests, activists, and Japanese language teachers.

Loyalty to the U.S. was determined by a poorly worded and badly administered questionnaire filled out by every Japanese American aged 18 and older. Two questions, numbers 27 and 28, determined whether a Japanese American was allowed to stay at the camp they were placed in or forced to relocate to this maximum-security prison.

Question 27: Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

Question 28: Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or disobedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?

The questionnaire caused chaos and turmoil throughout the camps, especially because the Issei, Japanese-born immigrants, had already been denied citizenship by the 1790 Naturalization Act. It was also perplexing for the second- and third-generation Japanese Americans. They had little connection to Japan, but their loyalty to America was controversially and unethically being tested.

Kyoko Oda, 80, a survivor of Tule Lake, was born into incarceration. It wasn’t until she had children and decided to go to UCLA years later that she began to transcribe her father’s stockade diaries from when he had been imprisoned at Tule Lake for three months. What started as a history class project for Oda evolved into an incredibly rare and valuable account of his experience, which is meticulously documented down to the contents of each meal. Tule Lake Stockade Diary was published as a book in 2021. Oda remembers the difficulty her father faced when answering the questionnaire.

Those who answered “no” (or anything other than “yes-yes”) to both questions were branded “the No-Nos.” Even beyond the segregation of Tule Lake, they faced ostracism and judgment from the Japanese American community for decades after the war.

Lester Ouchida, 87, is a survivor of the Jerome and Gila camps. His family’s story is a part of the California Museum’s exhibit on Japanese American incarceration in Sacramento, which includes the Florin produce sign that was part of his father’s thriving distribution business before the war. He often jokes that his early days of incarceration in Arkansas led him to adopt a Southern accent.

Ouchida’s uncle Pedro was a veteran of the 442nd regiment. Men who answered “yes” to questions 27 and 28 volunteered or were drafted into the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a unit entirely made up of Nisei (or second-generation Japanese Americans) that famously went on to become the most decorated unit of its size and service length in the history of the U.S. military.

Years later, Ouchida learned that the 442nd helped liberate Jewish prisoners from Dachau, Germany, one of the Holocaust’s first and longest-running concentration camps. This revelation moved me. How could Japanese American soldiers be freeing people in foreign lands while their own families were still imprisoned on U.S. soil?

Although several Japanese Americans challenged the constitutionality of the incarceration at the Supreme Court, only the case brought by Mitsuye Endo, a clerical employee at the California Department of Employment, succeeded. In Ex parte Endo — the ex parte signifying a type of legal proceeding — the court ruled that the U.S. could not detain “concededly loyal citizens.” The 1944 decision legally ended Japanese American incarceration but also put thousands of lives in limbo.

After the ruling, anxiety and fear reverberated throughout the barracks as families contemplated returning to cities and towns where they once had thriving businesses and communities. Many people were concerned about the hostility and anti-Asian hate of post–World War II America. In addition to experiencing the confusing grief of leaving places they had to tried to make into homes, many families were also dealing with the tremendous loss of relatives killed abroad in the atomic bombings of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In George Takei’s autobiography To the Stars, he describes how his mother, in the months prior to departing the camp, renounced her American citizenship after the passage of the Renunciation Act of 1944, also called the Denaturalization Act. Spurred on by “the relentless tide of anti-Japanese hysteria,” Takei writes, the “explosive and constitutionally indefensible piece of law” sought to get incarcerated Japanese Americans to “renounce their citizenship under the pressure-cooker conditions in the camps, so the legal path would be cleared for their eventual ‘deportation’ to Japan as ‘aliens.’”

In December 1944, the federal government announced the camps would be closing within six months. “Terror swept through the camp like an electric current,” Takei writes. In the Pacific, Japanese were still fighting U.S. soldiers, and anti-Japanese sentiment was strong in America. “The barbed wire fence that kept us incarcerated was ironically our protection as well,” he continues. “And now, that would be gone.”

Some incarcerees, like Takei’s mother, felt revoking their citizenship would force the U.S. government to keep camps like Tule Lake open, maintaining their families’ safety and protection. But when she was set to be deported, the family secured the assistance of Wayne Collins, an ACLU immigration attorney in San Francisco, who sued the government, arguing that thousands of denunciations of citizenship were coerced. Just two days before Takei’s mother was set to be shipped to Japan, the court ruled in her favor. Eventually her citizenship was restored and the family was kept from being torn apart.

When the camps closed in 1946, each detainee was given $25 and a one-way ticket to their chosen destination. Starting from scratch after losing so much weighed heavily on them and impacted generations of their descendants.

Bruce Matsui, 79, is one of more than 10,000 survivors of Manzanar. He worked for Cesar Chavez for a summer when he was 24 after returning from the Peace Corps in South America. He went on to receive his doctorate, and years later he developed an Urban Leadership PhD program at Claremont University, continuing his focus on making education accessible regardless of socioeconomic factors.

Matsui felt shielded from much of the racism of postwar America after his childhood in the camps because he grew up in Hawaii with his family on a plantation that employed and housed Japanese American farm workers.

It was a difficult transition for me coming from Hawaii where you’re part of the majority into a very small minority that was expected to behave a certain way. I just didn’t fit that category. And my uncles and aunts always cautioned my mom and dad about me, but my mom and dad never told me to change.

— Bruce Matsui

The redress process was complicated and consisted of an array of advocacy efforts that eventually led to the formation of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), appointed by Congress in 1980. Many activists, however, criticized the commission, noting that the need for redress and reparations was apparent without its formation, which some initially viewed as a possible stalling tactic by the government. Members of critical groups, including the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations, ultimately played a role in shaping the CWRIC. By the time it was established, efforts to seek reparations had been ongoing for decades.

In the late 1940s, a witness before Congress speculated that Japanese Americans had lost $400 million from their unjust incarceration, which would be about $7 billion in damages today — but the witness later admitted that number was entirely made up. To this day, no proper academic study has been dedicated to determining the true amount.

By 1965 the government had settled all individual claims for property loss, amounting to $38 million, but refused to address claims for lost wages, anticipated profits, personal injury, or pain and suffering. In 1983, the CWRIC suggested that property and income losses had been as much as $251 million before accounting for four decades of interest and inflation. Although experts say this number was still speculative, CWRIC’s efforts led President Reagan to sign the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. In 1990, President George H. W. Bush signed an official letter of apology, which was sent to every living survivor with a $20,000 reparations check (worth around $49,000 in 2025). The payment, however, could never compensate for the tremendous loss and painful memories that followed in the four-decade shadow after their incarceration.

I wanted to know how wartime incarceration from the time of birth or early adolescence could affect Japanese Americans’ acceptance of their identity. I was also eager to dig into research that represented an intersectional narrative: LGBTQ+ survivors of the incarceration camps. Overcoming religious and cultural stigmas, as well as potential remnants of internalized shame from incarceration, were apparent roadblocks for queer survivors like Mia Yamamoto.

Mia Yamamoto is a survivor of Poston. Years after her incarceration, she served in the 4th infantry division headquarters of the U.S. Army in Vietnam, and later pursued a career in criminal defense law. She has been working in the trial courts for more than 40 years and is the first trans defense attorney in California state history.

Yamamoto transitioned when she turned 60, coming out at her birthday party. She has said in many interviews that she did not want “to die as a coward.” She offered to find her clients a replacement lawyer if they no longer wanted to work with her. Every client stayed.

I could say in terms of my background that I think that my gender identity issues were buried very, very deeply and I actually spent a lifetime completely living in artifice and living a world to survive essentially, but just completely existing in a world that was completely without any transgender role models.

— Mia Yamamoto

Every year, Yamamoto — who has performed extensive human rights activism as a member of the LGBTQ+ community — attends the Transgender Day of Remembrance for individuals who have been murdered as a result of transphobia. Yamamoto has said life has been far from easy as “the first,” but she has tried to save lives by making herself as visible as possible.

Many Japanese American incarceration survivors found healing through writing memoirs, creating art that reflects their time in the camps, and sharing their stories with organizations like Densho, a Japanese American nonprofit digital resource center based in Seattle. These efforts have preserved their memories for their families and generations to come.

In the Little Tokyo neighborhood of Los Angeles, the Japanese American National Museum represents another significant effort to preserve memories and histories. For years, I passed this landmark institution during my commute downtown. One day, instead of driving past the building, I walked in.

My spontaneous curiosity led me to the Heart Mountain annual reunion, where I first met Jo Anne Naka and Hal and Barb Keimi. I had the honor of capturing the moment Naka stamped her name in the Ireichō, a sacred book that contains a comprehensive list of every person of Japanese ancestry who experienced incarceration. The stamp and the book symbolize the erasure that Japanese Americans endured, and entering their names in the book is meant to be a healing experience for survivors and their descendants. In February 2025, the Ireichō began a 20-month tour across the country as an interactive monument seeking out the remaining names that are missing.

At the museum, I witnessed a seemingly miraculous reunion. The large conference room was bursting with joy and resilience, just steps away from the bus station where some of these same survivors were uprooted from their communities. I saw multiple generations of families and recognized their lives had been defined not by this tragedy, but rather by how they found strength in rising above it.

I also learned of annual pilgrimages for survivors to revisit the camp sites. In 2024, descendants of Manzanar’s incarcerees gathered to play a game on its historic, since-revived baseball field. Jim Morita hopes to visit the field, where he has been invited to throw out a first pitch in the place he and his childhood friends called home 80 years ago. By then he will be just shy of his 100th birthday.

Through healing, many Japanese Americans decided to carry on customs and create new traditions as their families grew. Naka told me she had been hosting a New Year’s Day party for her family for more than 40 years, a celebration that combines Japanese and American customs.

Not captured in these portraits and interviews, the specter of the Alien Enemies Act — and how Roosevelt used it to incarcerate Japanese Americans — hung in the air. And with President Trump invoking the Act to deport immigrants, I’m reminded of something George Takei’s father said that always stuck with his actor and activist son:

One of the things that I use in my speeches a lot is my father quoted from Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address: ‘Ours is a government of the people, by the people, and for the people.’ [My father] said, ‘It’s a noble idea.’ That’s what makes our democracy a great democracy, a people’s democracy. But he said, ‘The weakness of our democracy is also in those words — a government of the people, by the people, and for the people — because people are fallible human beings. We make mistakes.’

— George Takei

In his autobiography, Takei recounts how years after their return to Los Angeles, he and his father were working on Adlai Stevenson’s 1960 presidential campaign when it was announced that Eleanor Roosevelt would be visiting the office. Everyone was excited — except Takei’s father, who went home early. The parents of these Japanese American incarceration survivors imparted wisdom and subtle forgiveness about this trauma but also felt the pain of incarceration for the rest of their lives.

After learning about the survivors’ upbringings, through their anecdotes and their personal archives, I set out to visit and document the remains of the Japanese American incarceration camps, as well as other historically relevant sites throughout California, Arizona, and Wyoming.

The landscapes are as unforgiving as the buildings are barren. But at Poston Camp I, built on Colorado River Indian Reservation land, I was stopped in my tracks by fencing around the camp’s perimeter. There, dozens of colorful origami cranes, or oritsuru, were tucked into the chain links. Tsuru for Solidarity, a Japanese American organization dedicated to ending detention sites and supporting immigrants and refugees targeted in the U.S., had made and placed the paper birds. They are intended to remind us that despite tremendous healing and hope, history is often repeated because of the quiet indifference of the majority.

Editor’s note: During the production of this feature, records and resources began disappearing from websites and databases that had long been maintained by the U.S. government. While this feature was independently reported, its publication would not have been possible were it not for the archives maintained by Densho, a grassroots nonprofit organization that has been documenting the history of Japanese American incarcerees since 1996. In Japanese, densho means “to pass on to future generations,” or “to leave a legacy.” Learn more at densho.org.